PLANES OF FAME: AVRO 698 Vulcan

Update: 2021/08/25 by Robert Kysela / CHK6

The current political situation in Europe between the NATO countries and the Russian Federation, under Vladimir Putin, is presently the subject of increasing media coverage with routine reports regarding tension between all parties involved. While the content of initial reporting was primarily political in nature, talk of military action has slowly but steadily increased. These are scenes, reminiscent of the Cold War and the global arms race, something the 50+ generation can well remember. However, the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent end of the Cold War in 1990/91 made any real possibility of full scale military conflict so remote that hardly anyone has considered it a real possibility for the past 25 years. A recent announcement however by the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, to modernise Russia’s nuclear arsenal due to the growing threat presented by NATO has brought the largely forgotten threat or nuclear war back into public consciousness.

In the early days of the cold war, long-range bombers were the only efficient method to deliver their fearsome cargo to their respective targets

R. Kysela

The Cold War was largely characterised by a policy of nuclear deterrence based on a principle of mutually assured destruction (ironically referred to as MAD) making any conflict involving the use of nuclear weapons not only unwinnable but also totally unthinkable. Both sides (the Western alliance under NATO and the Soviet Union with its Warsaw Pact states) deterred each other from attack through an continual process of nuclear weapons development and rearmament. Today, intercontinental ballistic missiles (mobile, underground or submarine launched) serve as the primary means of nuclear weapons delivery for the super powers.

In the early days of the cold war, long-range bombers were the only efficient method to deliver their fearsome cargo to their respective targets. The first aircraft to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were Boeing B-29 SUPERFORTRESS long range conventional heavy bombers with these aircraft being specially modified for these missions. Later, other aircraft such as the Boeing B-47 STRATOJET or B-52 STRATOFORTRESS, were specifically designed and built as strategic long range nuclear armed bombers to attack the Soviet Union and its satellite states. In addition to the Soviet Union and the United States, Great Britain also developed its own nuclear force. For this purpose, a series of strategic bombers were ordered shortly after the end of the Second World War, these aircraft were later designated as V-bombers. This designation was selected in reference to the Victory sign made famous by former British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill and had no connection to the V (retaliation) weapon designation used by Germany during the Second World War. A name beginning with the letter V was chosen for each of Britain’s new nuclear capable bombers (Vickers 667 VALIANT, Handley Page H.P.80 VICTOR and AVRO 698 VULCAN). The RAF’s V-bomber fleet, together with the USAF SAC (STRATEGIC AIR COMMAND), formed the backbone of the Western powers’ strategic nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Not long after commencing service, part of the British V-bomber fleet was retired or assigned to other tasks (the Vickers 667 VALIANT was taken out of service in 1964 due to technical defects, the Handley Page H.P.80 VICTOR was converted to operate as a tanker and remined active service until 1993). Only the AVRO 698 VULCAN remained in continuous operational service in its original role until 1984, although its employment and weapon payload changed considerably over time.

Originally, all V-bombers were intended to deliver free-fall nuclear weapons from high altitude, however as early as the mid 1960’s this strategy was seen as unfeasible due to the threat posed by high-altitude guided missile systems (e.g. S-75 DVINA; NATO code: SAM-2 GUIDELINE). A subsequent strategy envisaged the use of the BLUE STEEL nuclear stand-off weapon to be released relatively close to the respective target at very low-level. In this way, there was at least theoretically a better chance the aircraft and crew would survive to return home safely. Another survival feature applied to VULCAN during the late 1950’s was its distinctive white paint scheme intended to deflect thermal radiation from the nuclear explosion it had just delivered. Fortunately for mankind, the AVRO VULCAN was not used in this capacity, although the VULCAN did achieve the dubious distinction of having flown the longest bombing mission (a record later broken by the USAF’s Boeing B-52 STRATOFORTRES during the First Gulf War) in history.

During the Falklands War between Argentina and the United Kingdom, AVRO 698 VULCAN Mk.2B’s flew a total of seven missions (code named OPERATION BLACKBUCK) over a distance of 6,250 km from Ascension Island to bomb the airfield at Port Stanley. Although these attacks were completely ineffective from a military point of view (apart from punching a few holes in the ground), they were a great boost to British moral and demonstrated to Argentina that Britain was capable of performing such missions.

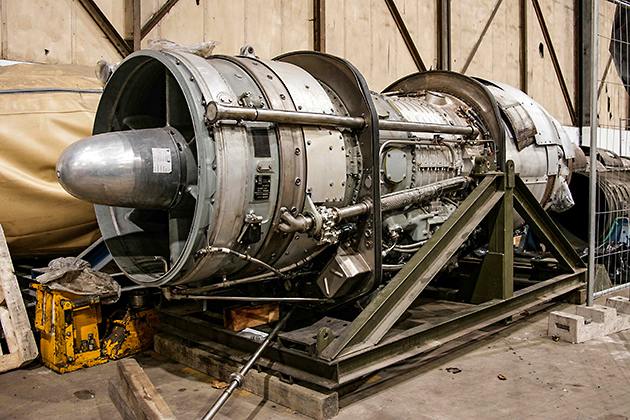

The final B.Mk.2 variant was powered by OLYMPUS Mk. 301 turbines providing a maximum of 89 kN of thrust

R. Kysela

The Vulcans original design was based on specification B.35/4 and was envisaged as a flying wing configuration (without a tail unit) that was strongly reminiscent of the designs of the Horten brothers. A delta-wing design was later agreed upon, now featuring a central tail unit, while its large delta wing incorporated a straight aspect ratio of 45°. After the first flight of prototype VX-770 on 30 August 1952 it quickly became apparent that the aircraft tended to vibrate during flight maneuvers at high speeds. As a result, the wing geometry was extensively modified, giving VULCAN its characteristic moth-like appearance.

While the first prototype was powered by four Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire engines, a second prototype, designated VX777, was equipped with the more powerful twin-shaft Bristol (later Rolls-Royce) OLYMPUS Mk. 100 axial engines. The final B.Mk.2 variant was powered by OLYMPUS Mk. 301 turbines providing a maximum of 89 kN of thrust. This gave the VULCAN sufficient power reserves, however pilots had to be careful with throttle input, otherwise the aircraft would quickly exceed its structural load limits at certain flight attitudes when full engine power was applied. Sadly, this was exactly what happened to the first prototype (XV770), when on 20 September 1958 the aircraft disintegrated in mid-air while performing a fast fly-past, sadly resulting in the death of the entire aircrew.

The Olympus engines also had a few peculiarities of their own that didn’t make life easy for the pilots. At 95% (+/-) power, the natural frequency of the low-pressure turbine coincided with the resonance of the engine. In the worst case, this can lead to major engine damage, which is why this particular power range was avoided by experienced crews. Despite these shortcomings, the Vulcan was a popular aircraft.

Designed to respond quickly in an emergency, a Vulcan crew could start all four engines within two minutes of a Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) sounding. A Palouste starter, a small gas turbine engine, blew highly compressed air directly into the turbines bringing them quickly up to speed, a process that takes just 30 seconds per engine. If no Palouste starter was available, Vulcan could also be started with its own onboard system. Engine No. 1 was started with the help of an internal compressed air supply and once running the other three turbines could be started simultaneously with the assistance of bleed air from the first engine. The life expectancy of the Olympus engines was calculated in “cycles”. In purely mathematical terms a cycle equates to a Hi-Lo-Hi profile, i.e. the engines entire operating range from idle to full load and back again. If the engines were ran at 100% power for take-off, no matter how long it lasted, then only one “cycle” was consumed.

Another interesting feature of the AVRO Vulcan, and one completely unbelievable and totally incomprehensible by today’s standards, was the lack of safety features for some of the five-man crew. While the two pilots were able to eject to safety in an emergency using Martin Baker Mk.4 ejection seats, the flight engineer, navigator and radar operator had to jump for their lives using conventional parachutes through an escape hatch in the floor. At altitudes below 2,000m, this proved to be deadly and for this reason alone service in a Vulcan was seen by some aircrew as anything but desirable.

On 18 October 2007, XH558 took off from Bruntingthorpe for its second maiden flight

R. Kysela

Vulcan remained in active service until 1984, after which only one aircraft (XH558) was sold to a private company based in Bruntingthorpe and was flown at airshows and public events for a further nine years . The importance this Cold War icon to the British was truly demonstrated by the incredible efforts made to keep this Vulcan in airworthy condition. This undertaking, while seemingly impossible in principle, actually did become a reality. To facilitate this the Vulcan-to-the-Sky Trust was founded with the aim of bringing XH558 back into the air through an elaborate and costly restoration project. Under the leadership of Dr. Robert Pleming, who sadly recently passed away, the trust actually managed to display this legendary four-engine bomber to the public over a period of (another) nine years, and all accomplished without any support from official bodies. On 18 October 2007, XH558 took off from Bruntingthorpe on its second maiden flight and for the next few years, XH558 was THE crowd pleaser for millions of spectators at selected events in the UK. A Vulcan display was absolutely spectacular with, as it was in the early 1990s, a display consuming a total of six of its 1,200 available cycles.

In an effort to extend engine life, or at least preserve them, the flight routine of the XH558 was slightly modified. The maximum engine power output during a display was reduced to 90% with hardly any effect on the dynamics of the demonstration. On the contrary – at 90% engine power the Olympus engines produced an loud, unmistakable but distinctive howl – much to the delight of the spectators!

No aeroplane can fly forever, so unfortunately this incredible episode had to come to an end and on 28 October 2016 with Vulcan XH558 landing for the very last time. Today, it is on public display in a specially built hangar at Doncaster Sheffield Airport, South Yorkshire where it is preserved for posterity.

To call the Vulcan a true icon is certainly no exaggeration. Its unmistakable appearance, its distinctive howl and phenomenal maneuverability for an aircraft of its size made it a show stopper par excellence! Fortunately, several Vulcans have been preserved in museums, and if you are lucky enough, one machine (XL426) can even be viewed performing high-speed taxi runs. This may not be as spectacular as a complete flight demo, but at least the machine can be seen in action. These taxi runs take place at London’s Southend Airport and are organised by the Vulcan Restoration Trust.

More information can be found here: www.avrovulcan.com

Robert Kysela / CHK6